State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies Report, Fall 2025

The Center for Connected Health Policy’s (CCHP) Fall 2025 Summary Report of the state telehealth laws and Medicaid program policies is now available as well as updated information on our online Policy Finder tool. The most current information in the online tool may be exported for each state into a PDF document. The following is a summary of the current status of telehealth policy in the states (and jurisdictions) given these new updates.

This edition reflects CCHP’s review of states conducted between late May and early September 2025. The executive summary also captures updates made in states since CCHP’s last annual State Telehealth Policy Summary in November 2024 (with review for individual states having concluded at various points before then). CCHP has produced this summary report since 2013. While it was previously released twice a year, it is now published annually each Fall, with three rounds of updates to each jurisdiction in the Policy Finder throughout the year.

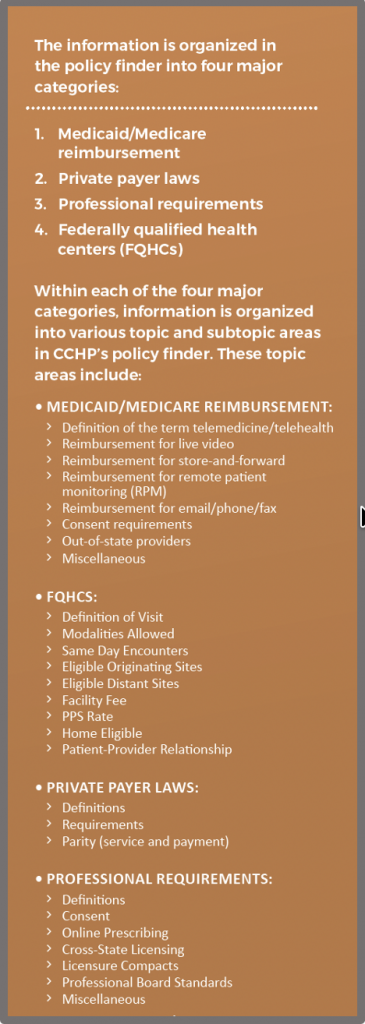

CCHP is committed to providing timely policy information that is easy for users to navigate and understand through our Policy Finder. Additionally, CCHP’s Policy Finder now features the reintroduction of the policy category related specifically to federally qualified health centers (FQHCs). CCHP began tracking this important category in the Fall of 2022, but had to pause updates last year when the funding for this work expired. However, thanks to renewed support from the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC), we’re once again able to offer this resource.

Read the executive summary

While this Executive Summary provides an overview of findings, it must be stressed that there are nuances in many of the telehealth policies. To fully understand a specific policy and all its intricacies, the full language of it must be read utilizing CCHP’s telehealth Policy Finder.

We hope you find the report useful, and welcome your feedback and questions. You can direct your inquiries to Amy Durbin, Policy Advisor or Christine Calouro, Senior Policy Associate at info@cchpca.org.

This report is for informational purposes only, and is not intended as a comprehensive statement of the law on this topic, nor to be relied upon as authoritative. Always consult with counsel or appropriate program administrators.

INTRODUCTION

The Center for Connected Health Policy’s (CCHP) Fall 2025 Telehealth Policy Summary draws data from its online Policy Finder. This edition highlights notable policy developments and trends that occurred between Fall 2024 and Fall 2025. Research for this report was carried out primarily from late May through early September 2025. The report provides a national overview of state telehealth policy, while CCHP’s Policy Finder offers state-by-state details, including information for all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands.

METHODOLOGY

CCHP examined state law, state administrative codes, and Medicaid provider manuals as the primary resources for the online Policy Finder, from which the findings in this summary are taken. Additionally, other potential sources such as releases from a state’s executive office, Medicaid notices, state PowerPoint presentations, bulletins or Agency newsletters were also examined for relevant information. While our methodology does not involve systematically searching Medicaid fee schedules for specific codes, when we encountered fee schedules in our research that explicitly identified telehealth reimbursement, we included them in our Policy Finder. Most of the information contained in the policy finder specifically focuses on fee-for-service; however, managed care plan information has also been included if available from the utilized sources.

Every effort was made to capture the most recent policy language in each state at the time it was last reviewed between late May and early September 2025. Note that in some cases, after a state was reviewed, it is possible that the state may have enacted a policy change that CCHP may not have captured. In those instances, the changes will be reviewed and catalogued within our online policy finder during the Winter update, and changes will be incorporated into the 2026 annual summary report. CCHP also reports on significant changes for each state that was updated in the previous month in our newsletter, which is released the second Tuesday of each month (subscribe to the CCHP newsletter).

Additionally, even if a state has enacted telehealth policies in statute, these policies may not have been officially incorporated into its Medicaid program. For purposes of this summary in regard to Medicaid, CCHP only counts states as reimbursing for a specific modality or removing a restriction if there is documentation to show that the Medicaid program has explicitly implemented a policy or statute. Requirements in newly passed legislation related to Medicaid will be incorporated into the findings of future editions of CCHP’s summary report once they are implemented in the Medicaid program, and CCHP has located official documentation confirming implementation.

KEY FINDINGS OVERVIEW

Since the onset of the pandemic in 2020, Medicaid programs across the United States have steadily refined and stabilized their telehealth policies, moving from emergency-driven flexibility to more permanent, structured frameworks. Since CCHP’s last 50-State Report in Fall 2024, states have continued to expand telehealth reimbursement in targeted areas—such as behavioral health, remote patient monitoring, and audio-only services—while also advancing cross-state licensing mechanisms through increased participation in interstate compacts and providing targeted licensing exceptions. At the same time, states are continuing to implement guardrails to ensure quality, such as clarifying provider responsibilities, consent standards, and modality-specific limitations, in an effort to balance expanded access with clinical integrity and oversight.

Findings include:

- Fifty states, Washington DC and Puerto Rico provide reimbursement for some form of live video in Medicaid fee-for-service. The Virgin Islands does not explicitly indicate they reimburse for live video in their permanent Medicaid policies.

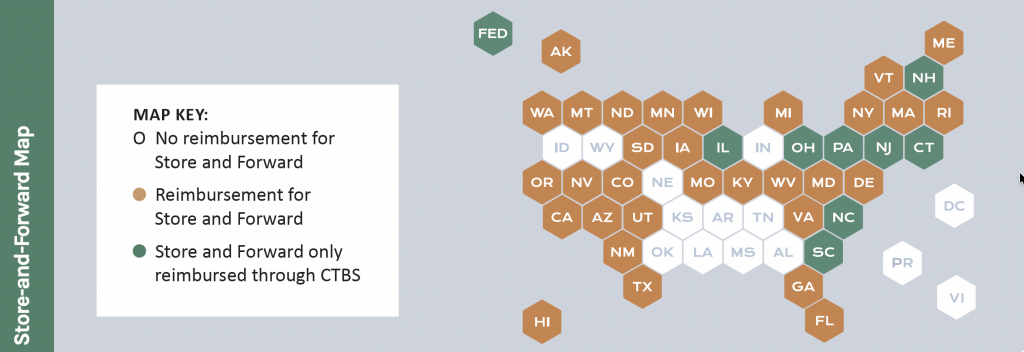

- Forty state Medicaid programs reimburse for store-and-forward. Connecticut and New Jersey are the states which added reimbursement for store-and-forward, although each in a limited capacity. Note that some states only reimburse store-and-forward through specific communication technology-based service (CTBS) codes. New Jersey was added as a state that reimburses for store-and-forward based on CTBS codes found in a New Jersey Medicaid Operational Manual.

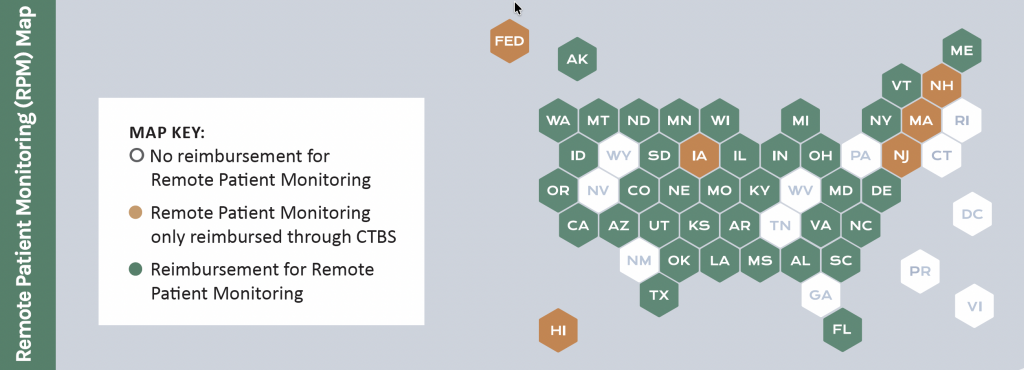

- Forty-one state Medicaid programs provide reimbursement for remote patient monitoring (RPM). New Jersey was added to the count since our 2024 update due to RPM codes found in a New Jersey Medicaid Operational Manual.

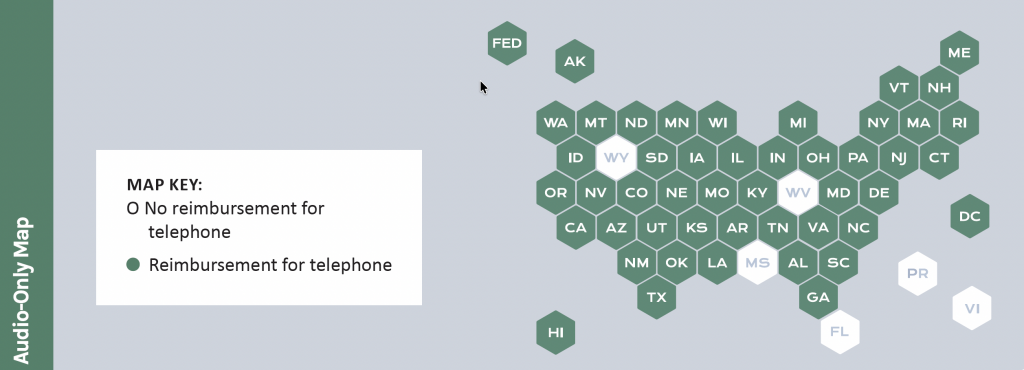

- Forty-six states and DC Medicaid programs reimburse for audio-only telephone in some capacity; however, often with limitations. Only one state, New Jersey, was added for audio-only reimbursement since Fall 2024.

- Thirty-two state Medicaid programs including Alaska, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Colorado, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin reimburse for all four modalities (live video, store-and-forward, remote patient monitoring and audio-only), although certain limitations may apply.

- Forty-four states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands have a private payer law that addresses telehealth reimbursement. Not all of these laws require reimbursement or payment parity. Twenty-four states and Puerto Rico have explicit payment parity. New Jersey was added since Fall 2024 due to an extension of payment parity requirements. Maryland also made a previously temporary payment parity requirement permanent.

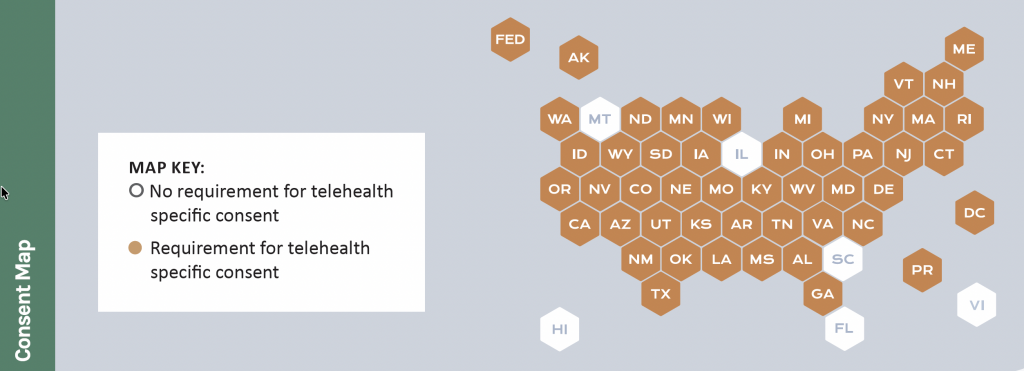

- Forty-five states, DC, and Puerto Rico include some sort of consent requirement in their statutes, administrative code, and/or Medicaid policies. No new states added consent policies that did not previously have one in either their Medicaid program or for at least one profession since 2024.

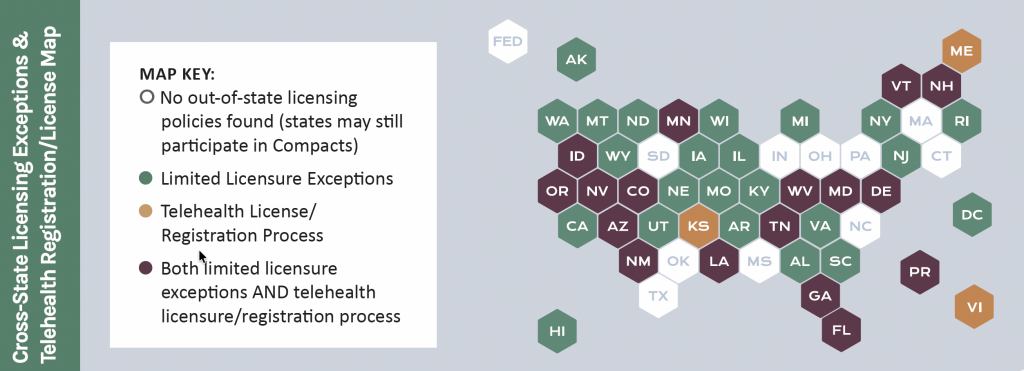

- Thirty-eight states, as well as DC and Puerto Rico offer some type of exception to licensing requirements. Note that while CCHP’s search of statute and regulations was confined to telehealth, if we happened to come across a more general licensing exception, we did include it in our reporting, and in this number. CCHP also found that eighteen states as well as the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico have telehealth-specific special registration or licensure processes as an alternative to full licensure for certain providers. To be counted in this number, the licenses/registrations did need to be specific to reference telehealth (or remote care) in some way.

- Many states continue to adopt or refine telehealth practice standards across a broadening range of health professions. While most states already have telehealth-related requirements in place for providers such as physicians, mental health professionals, and nurses, more state licensing boards are beginning to formalize standards for additional provider types. Recent developments show expanded regulation of telehealth practice for optometrists, dietitians, acupuncturists, social workers, and veterinarians, reflecting a wider recognition of telehealth as a regular mode of care delivery across disciplines.

- While CCHP does not track a specific count of states with telehealth prescribing requirements—due to the wide variation and numerous caveats across states—we do include online prescribing policies under the “Professional Requirements” category in our Policy Finder. Since Fall 2024, several states have implemented new or clarified rules around prescribing via telehealth, with particular attention to controlled substances. These updates often specify provider licensure, follow-up requirements, or the establishment of a prior in-person or telehealth relationship. Examples of these recent changes are detailed in the prescribing section below.

DOWNLOAD INFOGRAPH WITH KEY FINDINGS

While this report provides an overview of findings, it must be stressed that there are nuances in many of the telehealth policies. To fully understand a specific policy and all its intricacies, the full language of it must be read in its entirety, and can be accessed via CCHP’s telehealth Policy Finder. Below are summarized key findings in each category as of September 2025.

DEFINITIONS

How a state defines telehealth or telemedicine can significantly influence the breadth and limitations of its policies. In some cases, states embed restrictions directly within the definition, such as requiring services to involve “live” or “interactive” communication. These definitions can exclude modalities like store-and-forward and remote patient monitoring (RPM) from being recognized as telehealth, which often limits eligibility for reimbursement. Currently, all 50 states, along with Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, have adopted statutory, regulatory, and/or Medicaid-specific definitions for telehealth, telemedicine, or both—each shaping how care is delivered and reimbursed within their jurisdictions.

States vary in their use of terminology, often alternating between “telemedicine” and “telehealth,” with some using the terms interchangeably. Generally, “telehealth” is considered broader, encompassing both clinical and non-clinical services, while “telemedicine” may be reserved specifically for clinical care. There is also a growing use of more specialized terms prefixed with “tele,” such as “telepractice” or “teletherapy” for services like physical and occupational therapy, behavioral health, and speech-language pathology, as well as “teledentistry” for dental care. In psychiatry, “telepsychiatry” remains a common alternative. Meanwhile, Puerto Rico has introduced “cybertherapy” to describe patient-therapist interactions via communication technologies, and a few state Medicaid programs have begun using the term “virtual care,” though it is not yet widespread.

Adding to this evolving lexicon, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island recently adopted formal definitions of “telehealth” in specific contexts—despite previously defining only “telemedicine.” Pennsylvania’s new definition, introduced within its opioid treatment program, explicitly includes HIPAA-compliant video and audio-only platforms. Rhode Island’s update, tied to Medicaid policy for Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs), defines a telehealth visit as a 15-minute minimum encounter conducted by phone or videoconference that must meet criteria for clinical necessity and relevance to the client’s treatment plan. These developments highlight how states continue to fine-tune definitions based on program/practitioner-specific requirements, which can create added complexity for providers navigating multiple systems with differing terminology and reimbursement rules.

Historically, one of the most common limitations in telehealth or telemedicine definitions was the explicit exclusion of email, telephone, and fax as valid delivery methods. However, in response to the expanded use of audio-only (telephone) services during the COVID-19 pandemic, many states have since revised their definitions, either by removing the exclusion of telephone or by explicitly incorporating audio-only modalities into their telehealth or telemedicine definition frameworks. In some cases, CCHP observed that a state Medicaid program defines telehealth or telemedicine broadly enough to include store-and-forward, remote patient monitoring (RPM), and audio-only services—yet does not provide specific guidance on whether these individual modalities can receive standalone reimbursement. This lack of clarity can make it difficult for providers to determine which services are eligible for payment, despite being referenced and allowed in the definition.

MEDICAID REIMBURSEMENT

All 50 states, along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, maintain some form of Medicaid reimbursement for telehealth services. However, CCHP was unable to identify any permanent telehealth reimbursement policy in the Virgin Islands’ Medicaid program at this time. The scope and clarity of telehealth reimbursement policies continue to vary significantly across jurisdictions—with some states offering detailed, modality-specific guidance, while others maintain broader, less defined frameworks that may leave questions about implementation and coverage.

While many states have consolidated their telehealth policies into a single, easily accessible location since CCHP began researching Medicaid telehealth policies in 2012, some have only recently taken steps to streamline their guidance by incorporating comprehensive telehealth sections into their Medicaid provider manuals. For example, last year Delaware updated its Practitioner Manual to include a dedicated section on telehealth service policies, while New York released a standalone Telehealth Provider Manual for fee-for-service Medicaid providers. However, some states—such as Connecticut—continue to publish telehealth reimbursement information primarily through bulletins or dedicated Medicaid telehealth webpages, rather than in their provider manuals.

Additionally, several states have made policy updates that enhance provider flexibility and transparency. Missouri, through Senate Bill 79, revised its Medicaid telehealth statute to ensure that providers are not restricted in their choice of electronic platforms when delivering telehealth services. Both Alabama and California began requiring whether a provider offers telehealth-covered services to be listed in their Medicaid Provider Directories starting July 1, 2025, giving patients clearer access to virtual care options. (Congress’ 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act required Medicaid agencies to publish searchable provider directories by July 1, 2025.) Meanwhile, North Dakota updated its Telehealth Policies Document to reference a redesigned procedure code lookup tool, which now clearly identifies codes allowable for telehealth and audio-only services. This change replaces the state’s former static list of approved telehealth services, reflecting a move toward more dynamic and transparent policy tools.

STATE EXAMPLE:

SOUTH CAROLINA, updated each of its provider manual telehealth sections based on a single bulletin issued in December 2024 to announce updates to its telehealth policy following the public health emergency. The state made several permanent changes, such as continuing reimbursement for mental health services, developmental evaluation center (DEC) screenings, certain well-child visits, and telephonic E/M services using new CPT codes. At the same time, select flexibilities—including those for autism and therapy services—were extended for further evaluation through 2025, while others, like some telephonic assessments and early childhood services, were discontinued as of January 2025.

→ Live Video

Live video remains the most widely reimbursed form of telehealth across Medicaid programs in all 50 states, as well as in the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. As previously noted, the Virgin Islands is the only jurisdiction where explicit reimbursement for live video has not been identified. While coverage is nearly universal, the specific requirements and limitations tied to live video telehealth differ significantly from state to state. Medicaid programs often impose restrictions on live video—and other modalities—within three primary areas:

- The qualified healthcare providers who can receive reimbursement, including physicians, nurses, physician assistants, and more, as well as the location of the provider, known as the distant site.

- The eligible services for reimbursement, such as office visits or inpatient consultations, or services only related to behavioral health.

- The location of the patient, known as the originating site.

Although live video has long been the most established and extensively regulated telehealth modality within state Medicaid programs, major policy shifts in this area have been relatively limited over the past year. That said, states continue to make incremental refinements, frequently focused on clarifying existing policies—such as specifying covered services, eligible provider types, or detailed billing instructions. These nuanced updates reflect a continued effort to standardize implementation rather than overhaul existing frameworks, and several of these changes will be explored in subsequent sections of this report.

Eligible Providers

Many Medicaid programs have historically placed restrictions on which providers may deliver telehealth services. In recent years, however, there has been a clear trend toward broadening eligibility. Most states now allow a wide range of providers to furnish telehealth services, often without limiting the location from which those services are delivered. For example, Colorado recently expanded the definition of “Treating Practitioner” under Medicaid to include not only primary care providers but also specialists participating in the Accountable Care Collaborative. Eligible practitioners may now include medical doctors (MDs), doctors of osteopathy (DOs), nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician assistants (PAs) trained in specialty fields beyond primary care, provided they are involved in the member’s care. A growing trend across state Medicaid programs is the expansion of coverage for doula and community health worker providers, including their provision of telehealth services, such as policies implemented over the past year in Washington. For states that operate both fee-for-service and managed care programs, recent updates have clarified how telehealth is addressed under managed care, and within alternative payment methodology (APM) programs. For example, in a September 2024 notice, California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) confirmed that federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), rural health clinics (RHCs), and Indian Health Services will be reimbursed for telehealth services delivered through managed care plans, provided the appropriate modifier (93, 95, or GQ) is used. A February 2025 Medi-Cal Alert regarding the recently implemented APM program for participating FQHCs additionally references telehealth and FQHCs providing data regarding office visit codes billed with telehealth modifiers.

South Dakota has also revised its telemedicine manual to clarify coverage and provider requirements. According to the manual, certain services may now be delivered via telemedicine by Substance Use Disorder (SUD) Agencies, Community Mental Health Centers (CMHCs), and Independent Mental Health Practitioners (IMHPs). However, IMHPs cannot bill certain telehealth codes and may only provide services explicitly listed as allowable.

STATE EXAMPLES:

During this round of updates, both CONNECTICUT MEDICAID (CMAP) and MASSACHUSETTS MEDICAID (MassHealth) added reimbursement for doulas to deliver services including perinatal visits and labor and delivery support provided in person or via telehealth.

Eligible Services

In addition to broadening the types of providers eligible to deliver care via telehealth, many Medicaid programs have expanded the range of reimbursable services since Fall 2024. Behavioral health continues to be a major area of growth, with states like New Mexico adding evidence-based therapies such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), functional family therapy (FFT), and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT), as well as expanding coverage for medication-assisted treatment and inpatient psychiatric services. Similarly, Arkansas updated its autism and applied behavioral analysis (ABA) manuals to clarify which therapeutic services can appropriately be delivered through telemedicine, underscoring the careful balance states are taking between flexibility and safeguarding quality standards. Medicaid programs are increasingly expanding telehealth coverage within Mobile Crisis Team (MCT) services to strengthen community-based behavioral health crisis response. In Maryland, MCT is a 24/7 service available year-round that provides de-escalation, stabilization, assessment, and referral for individuals of all ages. Teams must include at least two members, with a licensed mental health professional (LMHP) either on-site or participating via telehealth, and follow-up may be delivered by phone, telehealth, or in-person. Similarly, New Jersey launched its Mobile Crisis Outreach Response Team (MCORT) to respond to 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline calls involving adults in non-life-threatening crises. The state’s Medicaid guidance includes billing scenarios that address the use of telehealth, offering providers clear instructions on coding and claims submission.

Beyond behavioral health, several states have turned their attention to oral and maternal health. Minnesota and Texas expanded teledentistry services, covering preventive counseling, hygiene instruction, and dental exams with synchronous audiovisual technologies. Colorado and Ohio broadened access to lactation support, recognizing telehealth’s ability to address postpartum care gaps.

STATE EXAMPLE:

CONNECTICUT MEDICAID will cover and reimburse Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) services provided by certified, enrolled dietitian-nutritionists under Public Act 23-94. These services may be delivered in person or through real-time audio/visual telemedicine, though providers must also be available for in-person visits if requested by members. Claims for telemedicine must use place of service (POS) codes reflecting where the service would have occurred in person (e.g., office – POS 11) and include either modifier 95 or GT.

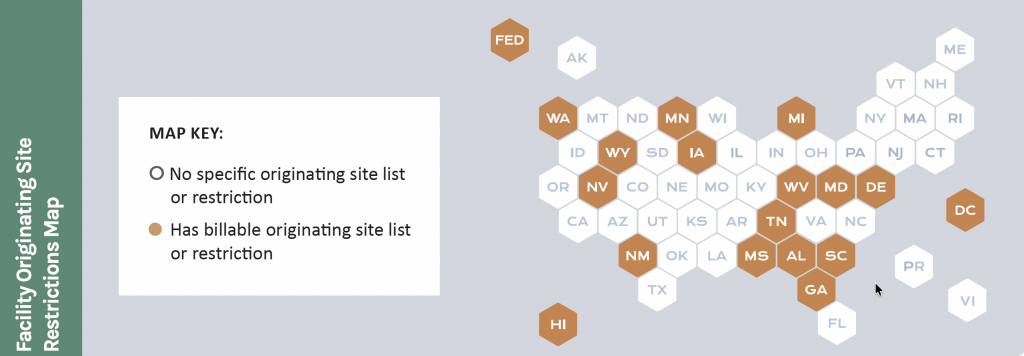

Geographic & Facility Originating Site Restrictions

Despite the overall decline in state Medicaid programs maintaining geographic restrictions on telehealth, two states — Hawaii and Maryland — continue to carry such requirements in their policies. These restrictions appear highly limited in scope and may, in some cases, be the result of outdated administrative language rather than intentional policy.

For Hawaii and Maryland, contradictions exist between statute and regulation, suggesting that administrative policies have not yet been updated to reflect legislative changes. For example, Maryland law requires Medicaid not to distinguish between rural and urban locations, yet as of CCHP’s Fall 2025 review, administrative code language still required beneficiaries seeking tele-mental health services to reside in a designated rural area or demonstrate that in-person psychiatric services were unavailable.

Rather than imposing geographic restrictions, many state Medicaid programs take the approach of defining which facilities may qualify as originating sites for telehealth. At present, sixteen states along with the District of Columbia maintain such lists. Over time, however, these lists have broadened to reflect more flexible policies. In several states, the range of approved sites now includes locations such as a patient’s home or school. In some cases, the lists serve more as guidance with Medicaid indicating that allowed sites include, but are not limited to the sites on the list. This signals a shift toward broader access even within frameworks that originally restricted originating site options.

Forty-eight states and the District of Columbia explicitly recognize the home as a permissible originating site under their Medicaid programs, though this allowance is frequently accompanied by added limitations, and providers generally cannot bill a facility fee for services delivered in this setting. This figure does not account for states that adopt broader language indicating coverage of telehealth from “any patient location” without specifically naming the home or residence. In many cases, states are considered to permit the home based on their acceptance of place of service (POS) code 10 — used to designate services provided in the patient’s home — when paired with the appropriate modifiers.

A growing number of states have updated their Medicaid policies to address how telehealth can be used in school-based settings, with some issuing detailed guidance on billing, modifiers, and place of service codes. CCHP found that 41 states and DC allow telehealth delivery of care in school-based settings in some capacity. For example, Oregon Medicaid revised its School-Based Health Services (SBHS) administrative code to add a section specifically dedicated to telehealth. The rule requires that services delivered via telehealth be reimbursed at the same rate as in-person care and allows use of either the GT modifier or modifier 93 for audio-only visits. It also mandates patient consent and creates special provisions to support the use of telehealth during a state or national emergency.

Pennsylvania has also refined its policies through updates to the School-Based ACCESS Provider Handbook. While the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services (DHS) historically emphasized in-person delivery of medical assistance services, the handbook now makes clear that some services may be rendered via telehealth in accordance with the state’s general policy. Pennsylvania provides specific billing instructions by requiring providers to differentiate place of service (POS) codes based on the student’s location at the time of service. POS 10 must be used if the student is at home, while POS 02 applies when the student is elsewhere, including when physically located in the school and connected remotely to the provider.

STATE EXAMPLES:

HAWAII enacted legislation barring geographic limitations within Medicaid, but the state’s Medicaid regulations continue to contain outdated language imposing such restrictions.

KANSAS MEDICAID requires providers at the distant site to bill using an appropriate code from the designated lists, paired with the correct place of service (POS). POS 02 must be used when telemedicine is provided outside of the patient’s home, while POS 10 applies when the service is delivered in the patient’s home. The GT modifier is no longer accepted for identifying telemedicine services. All telemedicine encounters are reimbursed at the same rate as comparable in-person visits.

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) & Rural Health Clinics (RHC)

Because Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and Rural Health Clinics (RHCs) bill as organizational entities rather than individual practitioners, they are sometimes omitted from state lists of telehealth-eligible providers. To address this, forty states and the District of Columbia have explicitly authorized FQHCs, RHCs, or both to serve as distant site providers under Medicaid. Additionally, 35 states and DC explicitly allow FQHCs to serve as originating sites for telehealth delivered services. Montana, for example, revised its FQHC and RHC manual to clarify that the originating site is defined as the member’s physical location, including the home. Claims must be submitted using revenue code 780 with procedure code Q3014 to account for the use of a room and telecommunication equipment, though Q3014 cannot be billed if the member’s home is the originating site. Texas also updated its Clinics and Other Outpatient Facility Services Handbook and Telecommunications Manual to expand telehealth use in specific contexts. The revisions authorize FQHCs and RHCs to provide telemedicine and telehealth services for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) clients if clinically appropriate, while also encouraging face-to-face visits when feasible. Texas further expanded its telemonitoring guidelines by adding FQHCs and RHCs as eligible home telemonitoring providers and adjusting prior authorization requirements. Policies related specifically to FQHCs is further summarized in CCHP’s Telehealth Policies and FQHCs Fall 2025 Factsheet.

STATE EXAMPLE:

INDIANA permits FQHCs and RHCs to bill for telehealth encounters if the service qualifies as both a valid FQHC or RHC encounter and a covered telehealth service. Encounter codes (T1015 or D9999) must be billed as usual, while each service within the encounter must carry the appropriate telehealth place of service (POS 02 or 10) and modifier (93 or 95). Payment for the encounter code is made at the facility’s prospective payment system (PPS) rate, while additional procedure codes on the claim will deny with explanation of benefits (EOB) 6096, as they are not payable under PPS methodology.

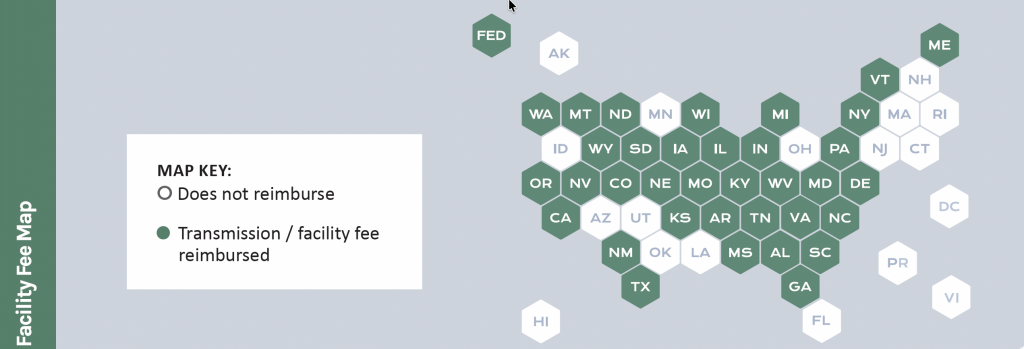

Facility Fee

Thirty-five state Medicaid programs provide reimbursement for a facility fee. State policies generally identify which types of facilities qualify to receive the facility fee and make clear that the payment does not apply when the originating site is the patient’s home or another non-clinical setting.

STATE EXAMPLE:

SOUTH DAKOTA has recently expanded the list of eligible originating sites for the facility fee to include inpatient hospitals and hospital based renal dialysis centers.

→ Store-and-Forward

Forty state Medicaid programs currently define and reimburse for store-and-forward services, with Connecticut and New Jersey among the states adding reimbursement since CCHP’s Fall 2024 update. This count excludes states that limit reimbursement solely to teleradiology, which is often treated separately from telehealth. Some states continue to restrict the definition of telehealth or telemedicine to “real-time” or “interactive” services, thereby excluding store-and-forward from coverage. Even in states that allow reimbursement, limitations may apply to certain specialties or provider types. For instance, Georgia only reimburses teledentistry delivered via store-and-forward for specified procedure codes. Some states also define telehealth in ways that technically include store-and-forward but stop short of issuing explicit reimbursement policy. Maine recently clarified in a Medicaid bulletin that text messaging does not qualify as an acceptable form of telehealth delivery, as it does not meet standards for audio-only or interactive audio-visual services.

Another way states have advanced store-and-forward reimbursement is through the adoption of Communication Technology-Based Services (CTBS). Eight states — Connecticut, Illinois, North Carolina, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina — reimburse store-and-forward under CTBS codes rather than stand-alone telehealth policy. New Jersey has a law requiring Medicaid to reimburse store-and-forward, but the only official Medicaid policy found thus far indicating implementation is coverage of various CTBS codes in the Medicaid fee schedule. Note that CCHP’s methodology does not typically include searches through Medicaid fee schedules (unless we happen to come across it through our Medicaid manual research). Therefore, if a state was reimbursing for specific CTBS codes but it is not mentioned in their telehealth policy, it is not generally captured in this report.

A growing policy trend is coverage of electronic consultations (eConsults), which often utilize store-and-forward to allow primary care providers to seek input from specialists without direct patient involvement. CMS guidance has clarified that Medicaid programs are permitted to reimburse eConsults, covered through CTBS codes, prompting several states to recently implement and expand coverage. New York, for example, issued multiple updates broadening reimbursement for eConsults in outpatient settings, including integrated consultations across physical and behavioral health, as well as interprofessional consultations involving dentists and medical providers such as physicians, NPs, and PAs. California updated its Telehealth Manual to cover CPT code 99452 for interprofessional electronic consultations. Colorado announced expanded eConsult coverage beginning July 2025 to support specialty-to-specialty consultations, though it also restricted durable medical equipment (DME) evaluations back to in-person delivery. Connecticut likewise issued a bulletin confirming that its Medicaid program will reimburse for eConsults. These developments highlight the increasing role of store-and-forward and related asynchronous modalities in expanding access to specialty care.

STATE EXAMPLE:

MICHIGAN MEDICAID lists asynchronous telemedicine service codes directly on the provider-specific fee schedules. Any additional coverage unique to particular programs is reflected on the corresponding program fee schedules and detailed within the relevant program-specific sections.

→ Remote Patient Monitoring (RPM)

Currently, forty-one states reimburse for remote patient monitoring (RPM) in their Medicaid programs. Since the Fall 2024 edition, only New Jersey was added due to remote monitoring codes found in a New Jersey Medicaid Operational Manual, though several states have made important updates and expansions. For example, Alabama revised its RPM Manual to clarify that provider orders— both initial and annual—are valid for one calendar year, with renewals required no later than 30 days after the previous order, and also updated the policy to include both an initial and annual home assessment. Virginia enacted two bills directing Medicaid policy changes: HB 1976 requires clarification that RPM for high-risk pregnant patients covers conditions such as maternal diabetes and hypertension, with utilization and cost reporting due by November 2025, while SB 843 tasks the state with developing a plan to expand RPM eligibility for chronic conditions. New York broadened its RPM coverage to include CPT code 99457, which may be delivered by clinical staff, reimbursing for the first 20 minutes of treatment management requiring interactive communication each month. New York additionally expanded its RPM reimbursement to outpatient settings, including FQHCs that have opted into Ambulatory Patient Groups (APGs). Maryland added several new codes to its RPM coverage while expanding access to include patients with any conditions and eliminating RPM prior authorization requirements. California has also recently expanded its RPM coverage in addition to removing its 21 and up age requirement for Medicaid RPM billing.

Reimbursement of RPM doesn’t always mean reimbursement of the same remote physiologic monitoring codes that Medicare reimburses. Arkansas passed SB 213, mandating reimbursement for remote ultrasound procedures using secure FDA-approved technology and requiring coverage of self-measured blood pressure monitoring (SMBP) for pregnant and postpartum women, including devices, training, and data transmission. Montana issued a provider notice on continuous glucose monitors, clarifying that CGM supply codes A4238 and A4239 may only be billed once monthly as a single unit of service and directing providers to CMS guidance due to a spike in claim denials. Texas also enacted HB 1620, requiring the state to evaluate the cost-effectiveness and clinical value of home telemonitoring before expanding reimbursement, with consideration of conditions such as end-stage renal disease, renal dialysis, and high-risk pregnancy, while ensuring collected clinical data is shared with the patient’s physician to maintain continuity of care.

It should be noted that five states—Hawaii, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and New Jersey —limit RPM reimbursement to specific Communication Technology-Based Services (CTBS) codes. Additionally, Alaska is included in the overall count of states reimbursing RPM due to listing self-monitoring in its manual, though anecdotal reports indicate the service is not actually reimbursed. Note that CCHP’s methodology does not generally include searches through Medicaid fee schedules (unless we happen to come across it through our Medicaid manual research). Therefore, if a state was reimbursing for specific CTBS codes (including RPM or RTM codes) but it is not mentioned in their telehealth policy, it is not captured in this report.

STATE EXAMPLE:

LOUISIANA: Passed House Bill 896 requiring Medicaid to cover remote patient monitoring (RPM) services for beneficiaries with one or more chronic conditions—including sickle cell disease, mental illness, asthma, diabetes, cancer, and heart disease—who also have a recent history of high-cost care, demonstrated by at least two hospitalizations, and who receive a provider recommendation for RPM-based disease management services. The legislation outlines specific eligible RPM services in greater detail.

→ Email & Audio-Only

Audio-only telehealth has expanded dramatically in Medicaid since 2020, though only one state, New Jersey, was added for audio-only reimbursement since Fall 2024. As of now, forty-six state Medicaid programs and the District of Columbia reimburse for telephone-based services in some form. A common theme across states is the move away from temporary emergency allowances toward more permanent policies, though the methods of implementation vary. For example, several states — including Michigan, Alaska, Montana, and Kansas — have discontinued the use of the temporary audio-only E/M codes (99441–99443) and transitioned to requiring providers to bill standard E/M codes with the appropriate modifiers. This shift aligns reimbursement more closely with in-person coding standards while still recognizing audio-only as a valid modality. Meanwhile, North Carolina and Ohio incorporated new American Medical Association (AMA) telehealth codes, which do not have an in-person equivalent, including audio-only codes, to expand options for therapy and counseling services. In contrast, the District of Columbia explicitly declined to cover the recently introduced AMA telehealth codes.

Other states have focused on updating statutory or administrative definitions to embed audio-only into their Medicaid programs. Missouri revised its statutory definition of telehealth to explicitly include audio-only alongside audiovisual technologies, reinforcing parity between modalities. Nebraska amended its administrative code to allow audio-only specifically for behavioral health and crisis management services, with conditions such as requiring an established provider–patient relationship and ensuring patients are never forced to use telehealth in lieu of in-person care. Similarly, Maryland enacted legislation converting temporary audio-only allowances into permanent coverage under its Medicaid program and certain insurers, while Ohio’s updated Managed Care Entities Telehealth Manual now permits audio-only interactions in alignment with Medicare rules. Additionally, Connecticut and Washington added new procedure codes to their audio-only eligible lists.

At the same time, some states have clarified limits on audio-only coverage. Washington, for instance, issued a provider alert specifying that audio-only telemedicine is not reimbursable under its birth doula benefit. Meanwhile, West Virginia ended its audio-only coverage allowed under emergency policies at the end of last year.

STATE EXAMPLES:

ALASKA, a newly released Medicaid fee schedule discontinues use of audio-only E/M codes 99441–99443 as of January 1, 2025. Providers must now use standard problem-focused E/M codes (99202–99205 and 99212–99215) for all telehealth modalities, with all required service components met to bill appropriately.

The ARIZONA Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS) added the newly created AMA telehealth and audio-only codes (98000–98106) to its Medicaid program’s reimbursable list. This reflects a broader national trend of states updating code lists to align with AMA standards, but implementation timelines and coverage decisions vary widely across jurisdictions.

→ Communication Technology Based Services (CTBS)

States continue to rely on the Communication Technology-Based Services (CTBS) codes established by CMS. CTBS encompasses services that, by definition, have no direct in-person equivalent because they are technology-specific (similar to the aforementioned AMA telemedicine codes). CTBS codes include e-consults, virtual check-ins (formerly HCPCS code G2012, now replaced by 98016), remote evaluation of pre-recorded information, audio-only service codes, e-visits, interprofessional consultations, and both remote physiological monitoring (RPM) and remote therapeutic monitoring (RTM) codes. States such as California, Connecticut, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Illinois, Massachusetts, North Carolina, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Utah, and West Virginia currently reimburse for CTBS codes (list is not comprehensive). Originally introduced by Medicare as an alternative to traditional telehealth, these codes have since been adopted by many state Medicaid programs.

Approaches to integration vary. Some Medicaid programs fold CTBS codes into their broader telehealth infrastructure, closely tracking Medicare’s coding framework for consistency. For example, Washington’s Health Care Authority and California’s Department of Health Care Services recently replaced G2012 with HCPCS code 98016, mirroring a similar coding change made by Medicare. Other states, however, treat CTBS separately, including the codes in fee schedules rather than their official telehealth policies. For the purposes of CCHP’s Policy Finder and this report, generally only CTBS codes explicitly incorporated into state telehealth policies have been included. Importantly, CCHP does not review state Medicaid fee schedules when compiling this data. In the State Summary Chart, the states that reimburse a modality solely through CTBS codes are denoted with an asterisk (*).

STATE EXAMPLE:

SOUTH CAROLINA Medicaid reimburses for a defined set of telehealth-specific CPT and HCPCS codes, including telephone codes 98966–99443, remote image evaluation code G2010, and brief virtual check-in code G2012. Coverage is limited to established patients, as these codes are not eligible for use with new patient encounters.

→ Additional Medicaid Restrictions

In addition to policies defining eligible providers, sites and services, many Medicaid programs maintain specific billing and administrative requirements for telehealth. These restrictions vary by state and territory and often include technology standards, billing codes, and certification processes.

MaineCare, for example, recently issued a provider bulletin emphasizing that while many covered services may be delivered via telehealth, they must be conducted through secure, encrypted telecommunications systems that comply with state and federal confidentiality laws. Providers are required to use technology sufficient to support effective care, act within their licensure scope, and continue offering in-person alternatives without limiting future access to services. For billing, Maine directs providers to use the standard procedure code paired with a GT modifier.

Other states have refined their billing requirements around place of service (POS) codes. Missouri HealthNet announced that, effective December 22, 2024, it will accept POS 10 for services provided in the patient’s home and POS 27 for care delivered in outreach or street-based settings. POS 02 will continue to indicate telemedicine services provided in other non-home locations, such as hospitals or clinics. Similarly, Kansas Medicaid clarified that retroactive to May 1, 2022, telephone evaluation and management codes (99441– 99443) must be billed with either POS 02 or POS 10 when provided within Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs).

CONSENT

Forty-five states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico include some form of telehealth consent requirement in their statutes, administrative codes, and/or Medicaid policies. The scope of these requirements varies significantly depending on the precise wording of the policy, with some applying broadly to all telehealth encounters and others limited to certain specialties or Medicaid programs. For example, Georgia’s HB 567 sets parameters for the use of telehealth in delivering dental services and requires authorizing or referring dentists to obtain consent from a parent or guardian when the patient is a minor. However, the law does not provide further detail on what that consent must include. Maine’s Optometry Board, in contrast, recently adopted telehealth practice standards that are more specific. These standards require providers to ensure that patients give appropriate informed consent for services delivered via telehealth—whether for a nursing assessment, physical exam, consultation, diagnosis, or treatment—and that such consent is documented in the telehealth record in a timely manner.

Louisiana has gone further by establishing detailed informed consent requirements in its practice standards for behavior analysts. The policy specifies that consent must address a range of issues, including contingency plans for technical failure, the scheduling and structure of services, potential risks, privacy and confidentiality, communication between sessions, emergency protocols, coordination of care, referrals and termination, record keeping, billing and third-party payors, as well as ethical and legal responsibilities across state lines. In addition, the new regulations require behavior analysts to be licensed in both Louisiana and the state where the client is located (if licensing is required there) and mandates that written informed consent be obtained and documented at the start of telehealth services. CCHP also found that Medicaid policies on consent this year often focused on telemedicine services involving minors. For example, Arkansas Medicaid’s Autism manual requires parental or guardian consent specifically for the delivery of services via telemedicine. Similarly, Oregon’s school-based health services administrative code mandates that, prior to delivering any covered service through telemedicine or telehealth, providers must obtain and document written, oral, or recorded consent from the child or their parent or guardian for the child or young adult to receive care using these modalities.

STATE EXAMPLE:

TEXAS House Bill 1700 directs all health professional licensing agencies to adopt standardized rules for telehealth consent documentation. These rules must address consent for treatment, data collection, and data sharing, and permit audio-only consent when clinically appropriate.

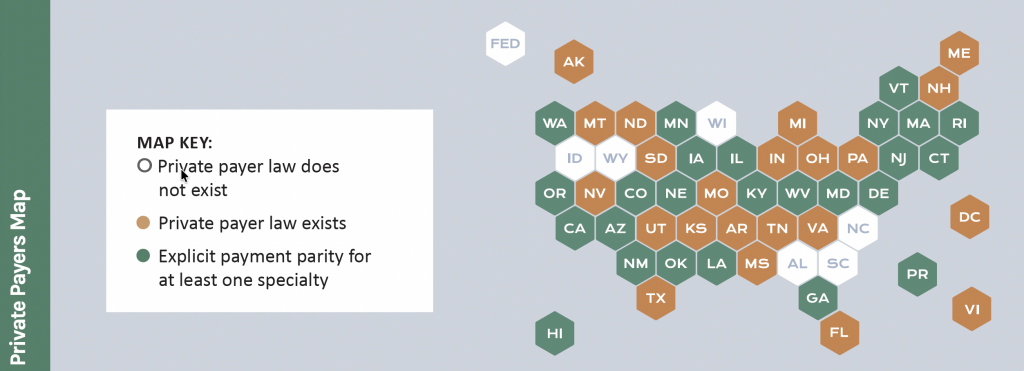

PRIVATE PAYERS

Most states now regulate how private payers must reimburse telehealth services, but their approaches vary significantly. As of this 2025 update, 44 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands have laws addressing private payer telehealth reimbursement. A common policy trend is the adoption of payment parity, requiring insurers to reimburse telehealth services at the same rate as in-person care. Currently, 24 states and Puerto Rico have parity requirements, making it the most frequent modification seen in private payer laws. Other states have pursued narrower changes, ranging from eliminating sunset provisions to clarifying coverage standards for out-of-state providers.

For example, Texas enacted House Bill 1052, which requires that beginning January 1, 2026, health benefit plans cover telemedicine, teledentistry, and telehealth services delivered from or to out-of-state sites on the same basis as in-state services. The coverage applies as long as the patient primarily resides in Texas and the provider is licensed and maintains a physical office within the state. Mississippi and Maryland made its private payer telehealth coverage law permanent by removing a scheduled repeal date. In New Jersey, payment parity requirements were extended through July 1, 2026, while New Mexico broadened its Telehealth Act, expanding the definition of eligible providers and encouraging both commercial insurers and Medicaid to incorporate telehealth coverage.

STATE EXAMPLE:

MONTANA took a straightforward approach to strengthening telehealth protections for patients. Through HB 60, the state prohibited insurers from applying higher deductibles, copayments, coinsurance, or other limitations to telehealth services than those applied to in-person care. This measure ensures patients accessing telehealth are not penalized with greater out-of-pocket costs, reinforcing telehealth as an equitable option for care delivery.

TELEHEALTH PRACTICE REQUIREMENTS

As states continue refining Medicaid and private payer telehealth reimbursement standards, professional licensing boards and health agencies continue to establish and specify provider practice standards regarding telehealth, such as those around consent, prescribing, and cross-state licensure. These rules are intended to ensure that care delivered remotely upholds the same standards of safety, quality, and professional accountability as in-person services. While there are common threads—such as licensing requirements, adherence to confidentiality and recordkeeping rules, and technology standards—states often tailor regulations to specific professions, resulting in a patchwork of approaches.

A consistent theme across states is the requirement that telehealth providers hold the appropriate license in the state where the patient is located. Wisconsin’s recent rules for optometrists and behavioral health professionals, for instance, specify that practitioners must be licensed in Wisconsin to treat patients in the state, while also adhering to other states’ laws when treating patients located outside Wisconsin. Similar provisions are found in Louisiana’s new standards for behavior analysts, which require licensure in both Louisiana and the state where the client resides, if that state requires licensure. Wyoming’s Board of Dental Examiners adopted comparable standards, clarifying that the practice of dentistry occurs where the patient is located and requiring that dentists establish a valid provider-patient relationship before initiating care via teledentistry.

Many states emphasize that telehealth must be delivered using secure technologies capable of supporting effective clinical care. Wisconsin’s rules, for example, hold providers accountable for ensuring that the technology used allows for safe, competent treatment. Arkansas extended similar principles into veterinary medicine, requiring veterinarians to formalize a client-patient relationship within a set period if care begins via telemedicine, thus balancing flexibility in emergencies with safeguards for continuity of care.

Several states have issued profession-specific practice rules tailored to unique needs. Colorado’s Senate Bill 194 formally defined teledentistry and authorized its use for assessments, consultations, and treatment planning when a licensed provider is not present at the originating site. A similar legislative approach was taken in West Virginia, which passed SB 710 to set forth various requirements for teledentistry as well. Ohio’s Chemical Dependency Professionals Board adopted an ethical code for telehealth, allowing services to begin without an initial in-person visit but requiring providers to screen clients for telehealth appropriateness. Washington established permanent rules permitting dietitians and nutritionists to provide services via telehealth when suitable for client needs, while North Dakota and Maine have taken steps to extend telehealth standards to optometry, veterinary care, and medical assistants in specific contexts.

Some jurisdictions stand out for distinctive approaches. Puerto Rico, for example, has delayed the implementation of a new telehealth certification requirement until December 31, 2025, giving time to build a system to credential providers across multiple health professions. Meanwhile, the Washington Medical Commission rescinded its Telemedicine Policy first issued in 2021, stating the policy was superseded by statutory law due to the legislature enacting the Uniform Telemedicine Act in 2024. Together, these evolving practice standards illustrate how states are balancing flexibility with accountability— ensuring telehealth is integrated responsibly into a wide array of professional fields while safeguarding patient safety and care quality.

LICENSURE

As telehealth utilization has expanded, many states have carved out exceptions to the traditional requirement that health care providers be licensed in the same state as the patient. CCHP’s review found that 38 states, along with the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, allow for some form of licensing exception. While our search of statutes and regulations focused on telehealth-related terms, we also included more general licensing exceptions when identified. These policies vary but often permit out-of-state providers to consult with or operate under the supervision of in-state providers, provided ultimate responsibility for care rests with the in-state professional.

Some states have enacted detailed statutory provisions that define the scope of these exceptions. For example, Alaska law allows physicians licensed in another state— or members of their multidisciplinary care team—to provide telehealth services to patients in Alaska under specific conditions. These include ongoing treatment or follow-up care for an established physician-patient relationship when an in-person visit has already occurred, or care related to a suspected or diagnosed life-threatening condition referred by an in-state physician. In such cases, both out-of-state physicians and their team members remain subject to the investigative and disciplinary authority of Alaska’s medical and licensing boards.

Other states take a narrower approach, limiting exceptions to specific professions or circumstances. Wisconsin permits nonresident providers to deliver marriage and family therapy, counseling, or social work services via telehealth to nonresident clients located in Wisconsin, but only if there is an established therapeutic relationship. Even then, this exception may be used no more than five days in a given month and no more than fifteen days total, and only if the provider is authorized to practice in their home jurisdiction.

These examples illustrate the diverse ways states balance access to care with regulatory oversight, ranging from highly detailed statutory frameworks for physician-led teams to tightly restricted carve-outs for behavioral health professionals.

In parallel, some states have gone further by establishing special telehealth-specific licensure or registration pathways for specific professions in their state. These processes create an alternative to full in-state licensure, allowing qualified out-of-state providers to deliver telehealth services under defined circumstances and regulatory safeguards. Eighteen states, the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico offer some form of special telehealth license or registration. To be counted in this number, the license or registration must specifically reference telehealth or remote care.

Georgia is among the states to recently implement a telemedicine license. Applicants must already hold a full and unrestricted medical license in another state and meet additional regulatory requirements. The license is limited strictly to the practice of telemedicine; in-person care for patients physically located in Georgia is prohibited unless in an emergency. Licensees are required to maintain records in accordance with state rules, follow professional conduct standards, and notify the Board of any restrictions or disciplinary actions in other jurisdictions. Issuance of the license is at the Board’s discretion, and denials are not considered contested cases, though applicants may appear before the Board.

Other states rely on simpler registration systems. In Minnesota, for instance, physicians licensed without restriction in another state may provide telehealth services to patients in Minnesota if they meet several conditions: they must not have had a license revoked or restricted in any jurisdiction, may not open an office or meet patients in Minnesota, and must annually register with the state medical board. This streamlined registration model emphasizes oversight while minimizing barriers for providers offering limited telehealth services.

Not all states have broadened their licensure processes. For example, Connecticut’s registration process for out-of-state mental and behavioral health providers delivering care via telehealth expired on June 30, 2025, leaving the state with no equivalent registration process to replace it. Other states have adopted extremely narrow approaches. In Maryland, the temporary telehealth license effective October 1, 2025 authorizes clinical professional counselors to provide services only to a student enrolled at an institution of higher education, and only if a therapeutic relationship has already been established for at least six months.

While some states have adopted targeted provisions for out-of-state providers, interstate licensure compacts remain the primary mechanism for enabling practitioners to work across multiple states and professions. These agreements generally allow eligible healthcare professionals to practice in other member states as long as they maintain an active license in their home state and obtain a special “compact” license. At present, CCHP tracks thirteen different compacts, each with its own eligibility requirements and application process. For example, the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact simplifies and expedites the application process for physicians, though doctors must still apply for and hold individual state licenses. We saw the largest jump in participation in the Dietitian Compact and Physician Assistant Compacts during this Fall 2025 edition of the report. Since last year, a new Compact was also added to CCHP’s tracking, the School Psychology Compact. So far, six states have joined. The School Psychology Compact requires at least seven member states to officially enact legislation to allow it to become operational. In addition, as some compacts are relatively new, not all are currently considered active and/or issuing licenses at this time.

STATE LICENSURE COMPACTS CCHP TRACKS:

- Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Compact: 4 state members (Not yet active)

- Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology Interstate Compact (ASLP-IC): 36 state members and Virgin Islands.

- Counseling Compact: 38 state members and DC. (Not yet active)

- Dietitian Compact: 15 state members. (Not yet active)

- Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Compact: 25 state members.

- Interstate Medical Licensure Compact: 42 states, DC, and the territory of Guam.

- Nurses Licensure Compact: 41 state members and the territory of Guam and the Virgin Islands

- Occupational Therapy Compact: 32 state members.

- Physical Therapy Compact: 39 state members and DC.

- Physician Assistant Compact: 19 state members (Not yet active)

- Psychology Interjurisdictional Compact: 41 state members, DC and the Northern Mariana Islands.

- School Psychology Compact 6 member states (Not yet active)

- Social Worker Compact: 31 state members (Not yet active)

* Not all states listed above may be currently operating the compact as many just recently passed legislation and have not had the opportunity to start the issuing process.

STATE EXAMPLE

NORTH DAKOTA allows certain physicians licensed elsewhere in the U.S. or Canada to practice via telehealth without first obtaining a North Dakota license, provided they meet specific conditions. These include:

-

-

-

-

-

- Continuation of care: Physicians may continue treating North Dakota residents if a provider-patient relationship was originally established in the physician’s home state. Care must be a logical continuation of prior treatment, not for new conditions requiring an in-person visit. Telehealth care may continue for up to one year before another in-person encounter is required.

- Temporary presence: Physicians may treat their established patients who are only in North Dakota temporarily for work, education, travel, or similar reasons.

- Pre-scheduled visits: Telehealth may be used in preparation for an in-person visit.

- Consultation: Out-of-state physicians may consult with a North Dakota–licensed physician who maintains responsibility for the patient’s care.

- Emergencies: Gratuitous services may be provided in emergency situations.

-

-

-

-

Physicians practicing under these exceptions are deemed to consent to North Dakota law, community standards of care, and the jurisdiction of the state medical board, including its disciplinary authority. See rule in policy finder for full details.

ONLINE PRESCRIBING

States continue to refine policies governing the prescribing of controlled substances and other medications via telehealth. A common theme across recent legislative and regulatory changes is the effort to balance access to timely care with safeguards to prevent misuse. While all states maintain some level of oversight and conditions, the exact parameters vary widely depending on the medication type, the patient-provider relationship, and the professional oversight structures in place.

Several states have clarified that controlled substances may be prescribed via telehealth under specific circumstances. For example, Maine expanded its Prescription Monitoring Program definition of “prescribe” to formally include telehealth encounters, thereby authorizing licensed professionals and veterinarians to prescribe controlled substances remotely under certain conditions. Delaware similarly tightened its oversight by requiring out-of-state practitioners to obtain a Delaware controlled substance registration even if they qualify under an interstate compact, practice privilege, or telehealth registration. Other states have taken more targeted approaches to prescribing authority. Mississippi authorized medical cannabis prescribing through Senate Bill 2748 for patients homebound or bedbound, while Pennsylvania allowed initial opioid treatment program exams for buprenorphine or methadone to be conducted remotely, provided a full in-person exam follows within 14 days and federal standards are met. In Alabama, the Board of Medical Examiners clarified that the in-person requirement for prescribing controlled substances can be satisfied if qualified medical personnel are physically present with the patient at the originating site during the telehealth encounter.

Texas regulations emphasize continuity of care and technology standards: prescriptions must be grounded in a physician-patient relationship and, for chronic pain, telemedicine visits must use two-way audiovisual communication unless the patient is under ongoing care and was seen in the last 90 days. Note that providers must also comply with federal requirements for prescribing controlled substances via telehealth, which generally include conducting an initial in-person visit or meeting one of the limited exceptions allowed under permanent law.

STATE EXAMPLE:

HAWAII passed HB 951 permitting healthcare providers to prescribe a limited three-day supply of opiates via telehealth for patients already evaluated in-person by another provider within the same medical group. This policy aims to ease access to short-term pain relief while minimizing risks of overprescribing and misuse.

To learn more about state telehealth related policy and for the most up to date information, visit CCHP’s telehealth policy finder tool.

< BACK TO REPORTS